Longread

Strip cropping harvest requires more flexibility from food processing companies

Does strip cropping create additional challenges for post-harvest food processing? Scientists from Wageningen Food & Biobased Research investigated three wheat harvests for that purpose. The wheat from strip cropping proved more difficult to clean and separate, but baking tests showed that the flour is on par with commercial varieties when baking bread.

Diversity in the field has a positive impact on ecosystem functioning, and strip cropping is an accessible and relatively simple way for farmers to grow more diverse crops on one field. A variety of crops are grown in strips of 3-6 metres wide. Five years of research on strip cropping shows that yields are comparable to those of the more common monocropping approach. Strip cropping also further improves biodiversity on land, one of the key challenges of our time. Natural enemies know how to find pests such as aphids more quickly and diseases, such as phytophthora in potatoes, spread more slowly.

'Farmers who switch to strip cropping also report that they get more happiness out of their farms,' says Dr. Ir. Dirk van Apeldoorn of the Farming Systems Ecology group at Wageningen University & Research (WUR). 'That also seems like a very valuable return to us, especially at a time when farmers are experiencing a lot of societal pressure.' So, can all farmers switch to this new form of arable farming now? In principle, yes, of course, but there are still questions to be investigated. Not least among them: what possible implications does strip cropping have for post-harvest food processing?

If we want farmers to widely embrace strip cropping, we need to know what barriers still exist in the processing chain

Cleaning and separating harvests

Mira Theunissen is a researcher at the Food Technology group of Wageningen Food & Biobased Research. She is working on the Rethink Food Processing project, and for her, the central question is exactly that: what does strip cropping mean for food processing? 'If we want farmers to widely embrace strip cropping, we need to know what barriers still exist in the processing chain: what makes harvests from strip cropping more difficult to process into a food product, such as bread or a vegetable mix?' The researchers are surveying the challenges across the chain, and are now focusing on the processing steps just after harvest: cleaning and separation.

In strip cropping, this cleaning and separation process is very important, because the number of impurities is higher than in the harvest of large monocultures. For example, neighbouring crops can be carried along, as a relatively large proportion of the harvest is derived from the edges of the strip. 'We have also examined harvests from mixed cropping, where two complementary crops, in this case wheat and faba beans, are intermingled. These can potentially be separated by size, but there is a risk of a shrivelled faba bean ending up among the wheat or a wheat grain sticking to a gnawed-on bean.'

That kind of cross-contamination requires serious attention from a food safety perspective, especially in terms of allergens. 'If even the slightest bit of wheat ends up among a legume crop, it can no longer be sold as gluten-free.'

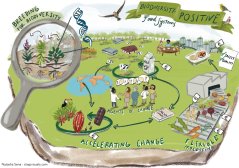

Investing in biodiversity-positive food systems

The 'Rethink Food Processing' project, led by Dr Anke Janssen of the Food Technology group, is part of the investment theme Biodiversity-Positive Food Systems. To this end, Wageningen University & Research invests in research that provides fundamental knowledge for innovative pathways that strengthen biodiversity and ecosystem services in fields, farms, landscapes and value chains. The theme is coordinated by prof.dr.ir. Liesje Mommer, Professor of Belowground Ecology & Biodiversity figurehead, and dr.ir. Marleen Riemens, Team Leader Crop Health.

Comparable with commercial products

Mixed crops should be harvested when both crops are at optimum maturity. If there is a difference in maturity, there is an additional step in processing, as the crop has to be dried first. Difference in maturity also affects the functionality of a crop. 'It produces variations in quality. Wheat flour derived from strip cropping is less compatible with standardised processing procedures: these are set for the more uniform product from monocultures. In the future, food processing companies will have to become more flexible, for example by tailoring their recipes to the properties of their raw materials.'

Theunissen and her colleagues discovered those necessary adjustments when they experimented with wheat processing. 'We cleaned, separated and processed harvests from three different growing systems into mini-breads and biscuits. These were harvested from a strip with one variety of wheat, a strip with two varieties mixed together and a strip of mixed cropping, where wheat grew mixed with legumes.' The baking trials produced bread and biscuits of similar or sometimes even better quality than commercial reference flour. To make the loaves rise properly, however, the recipes had to be adjusted, for example by adding extra gluten.

More protein thanks to legumes

There was also the question of whether mixed cropping yields could be processed unseparated. For instance, would it be possible to grow the ingredients of a vegetable mix together and process them simultaneously? Grown together in the field to end up combined in a soup packet. 'Co-processing two crops from one strip without separating them first seems almost impossible,' Theunissen explains. 'Proper cleaning virtually always results in separation. And even if cleaning could succeed without separating, the peeling or grinding process afterwards remains a huge challenge.'

Food processing companies cannot continue to produce in the same way if they want to process this crop

However, mixed cropping can provide another advantage. 'Pulses such as faba beans provide more nitrogen in the soil, while cereals use nitrogen as a building material to make proteins. This could result in an interesting trade-off.' In fact, the researchers saw that the wheat grown among the faba beans contained more protein. During the baking tests, that wheat produced excellent mini-breads, but the biscuits made from blended wheat flour were rather firm. This is presumably also the result of the increased protein content, the researchers believe.

Standardisation phase-out

'Strip cropping is more diverse in all aspects: more variety in products, more biodiversity, but also differences in maturity. That's a fact,' Van Apeldoorn stresses. 'Food processing companies cannot keep producing in the same way if they want to process this yield. It requires creativity and innovation not only from the farmer, but also further down the chain.' That is also the main conclusion Theunissen and her team drew. Far-reaching standardisation in processing will have to give way to tailor-made solutions to properly deal with these strip crops, which have so many benefits for the ecosystem.

'But adjustments can also be made in other parts of the chain between the farmer and retail. Farmers now produce for warehouses, but what if they could produce far more directly for consumers? What if processing was no longer done in large plants, but on the farmer's own land?' Consumers will also have to get used to a new situation where not every product is always available. 'A more diverse diet supports a more diverse field, we could say.'