News

EU ABS Regulation: human microbiota and pathogens

Human genetic resources are outside the scope of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), Nagoya Protocol and EU ABS Regulation, but human microbiota and pathogens occurring on or in humans are not considered to be human genetic resources and may be in scope of the EU ABS Regulation. What do you need to keep in mind when using genetic resources associated with humans?

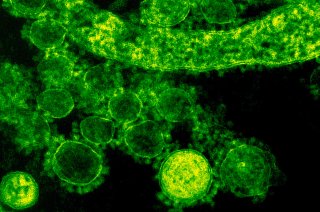

Human microbiota

In the context of the EU ABS Regulation, the term ‘human microbiota’ is used to refer to all microorganisms (such as bacteria, fungi, and viruses) residing on or in the human body, and ‘microbiome’ to the collective genomes of those microorganisms (i.e. the collective genetic resources). The microbial diversity is unique to each human individual and may change during the lifetime of this person.

While associated with human beings and essential for the well-being and survival of the human individual, the human microbiome represents genetic resources of non-human nature. The human microbiota is thus to be considered separate from human genetic resources, since it comprises distinct and different organisms. However, because of the symbiotic interaction between the microbiota and the human body, which results in a unique composition of microbiota in each individual, special conditions apply under the EU ABS Regulation to the use of human microbiota.

When studies focus on the microbiota from an individual human as a whole, and do not focus on individual taxa, such studies are considered to be out of scope of the EU ABS Regulation. However, when research and development activities are carried out on individual taxa isolated from a sample of the human microbiota, this isolate no longer represents the unique microbial composition characteristic of an individual human, and the studies are considered to be within scope of the EU ABS Regulation.

For example, a pharmaceutical company studies the composition of the gut microbiota in human faecal samples that are obtained from individuals, to explore the relationship between the microbiota and mental health. As the gut’s microbiota is unique for every individual, this study is out of scope of the EU ABS Regulation. In another study, the gut bacterium Lactobacillus rhamnosus is isolated from several samples and tested for its ability to inhibit attachment of Escherichia coli to human colon cells. As this study is focussed on an individual taxon, rather than the human microbiota, it is considered to be in scope of the EU ABS Regulation.

For more information, see section 2.3.1.7 of the EU Guidance.

Human pathogens and pests

When pathogenic organisms or pests present on a human are introduced unintentionally to a place in the EU, they fall outside the scope of the EU ABS Regulation, as there was or is no intention of introducing or distributing the harmful organisms as genetic resources. This is the case, for example, when travellers who are unknowingly infected with a virus travel to an EU country. However, if the pathogens or pests are established in situ in an EU country following introduction, utilisation of these genetic resources may be in scope of that country’s ABS legislation. For more information, see section 2.3.1.5 of the EU Guidance.

In case of a pandemic influenza virus, the genetic resource may be covered by the Pandemic Influenza Preparedness (PIP) Framework. Because the PIP Framework is recognised by the EU as a specialised ABS instrument, there are no obligations related to the EU ABS Regulation when the genetic resource is covered by the PIP Framework. Read ‘Minimising your administrative burden: specialised ABS instruments’ for more detailed information.